LGBTQ scientists who changed the world

October is LGBT history month in Canada and the U.S., a month-long celebration to honour the many contributions the LGBTQ community has made in society.

The month is selected to coincide with National Coming Out day on October 11.

In honour of it, here are some LGBTQ scientists who changed the world.

This post will be updated with new scientists throughout the month, so check back frequently.

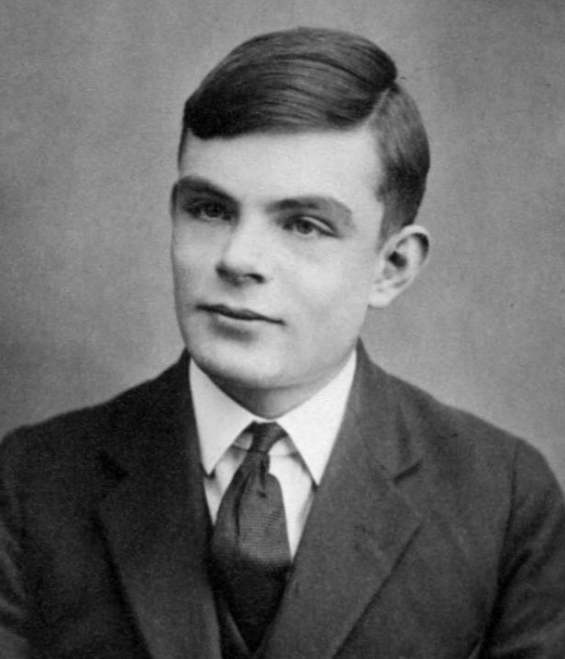

Alan Turing (June 23, 1912 – June 7, 1954) was a ground-breaking mathematician, computer scientist, and theoretical biologist.

Of all his achievements, it is likely his code-breaking work at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire during WWII that he is best known for.

Turing was born in 1912 in London, England and studied at Cambridge and Princeton Universities. In 1939, he began a full-time job at Bletchley, working on top-secret projects that deciphered German codes sent to allies.

His work focused on cracking messages sent by the German Armed Forces on a machine called The Enigma. Turing was instrumental in the invention of a device called the Bombe, which was created in collaboration with Gordon Welchman. It helped make code-breaking easier, allowing Bletchley officials to read German Air Force signals and assist war efforts.

In addition to countless other code-breaking innovations, Turing invented the universal Turing machine, which is considered to be the starting point for stored-memory computers. His work at the National Physical Laboratory is regarded as the predecessor of the modern computer.

In 1952 Turing was arrested for homosexuality, which was then considered illegal in Britain. He was found guilty of ‘gross indecency,’ but avoided prison by agreeing to undergo a horrific chemical castration.

Turing was found dead in his home in June 1954 at the age of 41 in an apparent suicide. On Christmas Eve 2013, the Queen signed a posthumous pardon for him.

His life was chronicled in the 2014 film The Imitation Game, starring Benedict Cumberbatch.

Ben Barres, MD, Ph.D. (Sept. 13, 1954 – Dec. 27, 2017) was the chair of the neurobiology department at Stanford University School of Medicine and the first openly transgender scientist in the National Academy of Sciences.

Barres’ research into the important role glial cells play in all stages of a neuron’s development is said to have revolutionized the study of neuroscience.

He was known for his rigorous work ethic, often working until 3 a.m.

In an article by Standford University, Barres is described as a devoted mentor who championed for women in science.

He died of pancreatic cancer at the age of 63 in 2017. In 2018, his posthumously published memoir, The Autobiography of a Transgender Scientist, was published. It documents his 1997 transition from female (Barbara) to male, and the unique insight gained through working as a neuroscientist as both a woman and then a man.

“When I decided to change sex 15 years ago I didn’t have role models to point to,” he said in 2012.

“I thought that I had to decide between identity and career. I changed sex thinking my career might be over. The alternative choice I seriously contemplated at the time was suicide, as I could not go on as Barbara.” In the same interview, he added: “young people should never let anyone make them feel bad about who they are — their differences are often their greatest advantages in life.”

Alan Lucille Hart (October 4, 1890 – July 1, 1962) was a U.S. physician and tuberculosis (TB) researcher. In the winter of 1917-1918, he was one of the first female-to-male transgender people to undergo a hysterectomy, living the rest of his life as a man.

Born Alberta Lucille Hart, Alan enrolled in Albany College in 1908, and transferred to Standford two years later, where he established the university’s first female debate club.

After finishing college Hart attended Oregon Medical School and, in 1917, became the first woman to receive the Saylor medal for achieving the highest standing in every department in the entire school.

In 1918, not long after his transition, he married Inez Stark.

The couple was forced to move frequently when Hart’s gender was questioned. This made it difficult to establish a medical practice and, in 1923, Stark filed for divorce.

He married Edna Ruddick in 1925. Three years later, Hart received his master’s degree in radiology from the University of Pennsylvania and became director of radiology at Tacoma General Hospital.

In the early 1900s, X-rays were used to detect tumors and fractures, but Hart was interested in their ability to screen for TB, which was one of the top killers in the U.S. at the time. He became an expert on tubercular radiology and published numerous papers on the value of X-rays as a TB detector.

The use of X-rays enabled early detection, which significantly reduced death rates.

Hart died from heart failure in 1962. When Edna died in 1982, she left most of her estate to the Medical Research Foundation of Oregon in memory of her husband.