Study finds common approach to diversity & inclusion in academia caters to white students and faculty

"Students, universities, and policymakers should consider cultivating a culture that values diversity for a more balanced mix of reasons."

Updated: 04.21.21 8:00 a.m.

It has been nearly a year since former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd. Since that time, much has changed — but much has remained the same. This month the world is reeling from the execution of 20-year-old Duante Wright, shot and killed by police officer Kim Potter.

At the time of this writing U.S. police have killed at least four other unarmed Black people in 2021 [UPDATE 04.21.21: that number now sits at five]. The global protests sparked by Floyd’s murder in the summer of 2020, and the ongoing, senseless deaths of Black Americans, have caused the world to pause and reassess. For some, that has resulted in positive change.

Related: Does your organization really want to end anti-Black racism? 4 ways to tell

One example of that includes the American Health Association (AMA) acknowledging racism as a public health threat. The organization has committed “to actively work on dismantling racist policies and practices across all of health care.” That follows years of lobbying and numerous studies identifying a link between racism and poor health outcomes.

But in other institutions, diversity statements and initiatives have been empty and performative.

In January, the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education (COACHE), based at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, released a review of a job satisfaction survey completed by faculty at all two and four-year colleges in the U.S. associated with COACHE. It found “significant disparities” in how white and non-white faculty members perceive diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) progress on college campuses, with 73 per cent of white faculty members saying there is visible and sufficient DEI support on campus. Only 55 per cent of their Black colleagues felt the same way.

About 78 per cent of white professors said their departments are committed to expanding DEI initiatives, while only 58 per cent of Black faculty agreed.

“The surprise is how wide the gap is between white faculty who feel that their colleagues and leadership are fully in support of diversity and inclusion and Black faculty who don’t agree that their colleagues and leadership are doing what they can,” Kiernan Mathews, director and principal investigator of COACHE, said in a statement on the Harvard Graduate School of Education website.

“These data show an 18- to 20-point difference in the percentage of white faculty and Black faculty who agree that leadership and colleagues are committed to supporting and promoting diversity on campus. It’s a stark difference in what white faculty feel to be true and what Black faculty know to be true with respect to the support and promotion of diversity.”

And now, a new study out of Princeton University finds many DEI programs, some of which were newly instated in the aftermath of Floyd’s murder, are catering to (most) white people — not the underrepresented groups they were supposedly created to support.

The paper looked at eight studies involving 1,200 participants and found many institutions are centering their DEI initiatives around the narrative that “diversity enhances student learning.” But researchers say that view tends to be preferred by white, not Black, students, and aligns with “better relative outcomes” for white people.

Per a statement from Penn, researchers looked at two different approaches to diversity. The first was an ‘instrumental’ rationale, “which asserts that including minority perspectives provides educational benefits,” the authors say. The second was a ‘moral’ rationale, which, “often invoking a legacy of racial inequality, argues that people from all backgrounds deserve access to a quality education.”

Instrumental rationales appear to be the dominant approach and favoured by white people. The authors say institutions should instead focus on the nuanced reasons diversity matters, including a more justice-centered approach, rather than just touting the benefits DEI efforts can provide.

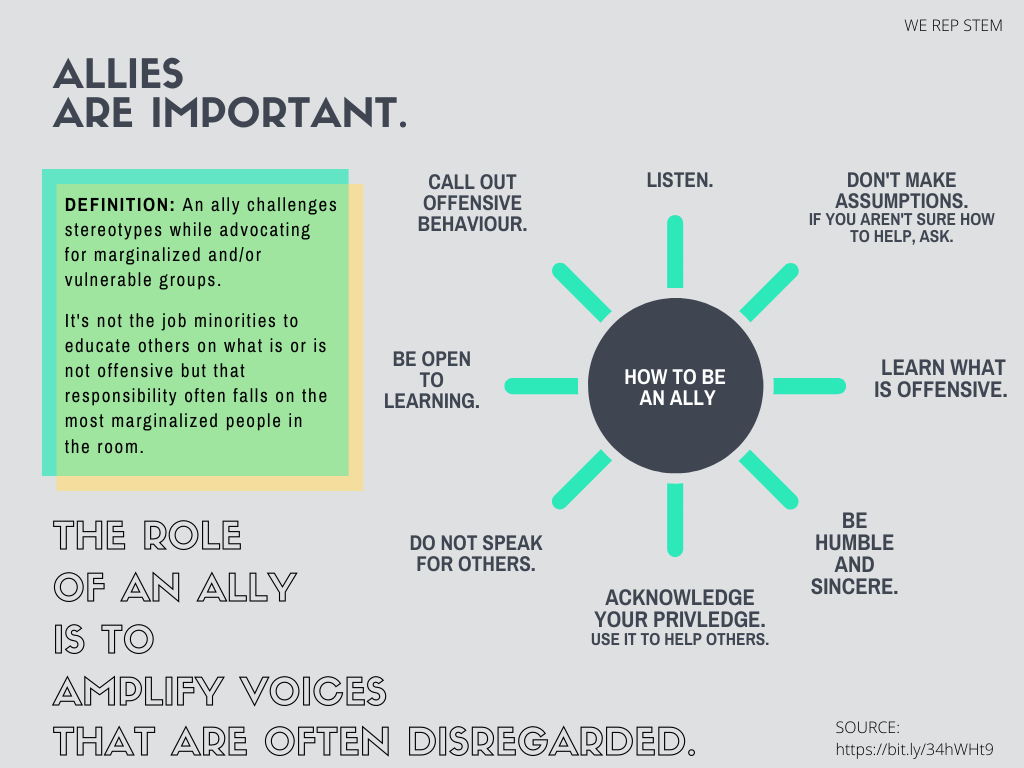

That, of course, involves getting comfortable with being uncomfortable, one of the pillars of effective and authentic allyship. In order to avoid mistakes of the past, the past needs to be analyzed in full.

The road to becoming an authentic ally was never meant to be paved with marshmallows and cotton candy.

Allyship is a skill that needs to be developed, just like any other. And confrontation, and the discomfort that comes with that, can be an effective strategy. This was evidenced in a July 2020 study which found white people who are confronted about a sexist or racially insensitive comment they made are more likely to reflect and avoid making biased statements in the future.

In the recent Penn study, participants were told to imagine themselves as university students and read and react to a series of instrumental and moral diversity statements. In additional studies, questionnaires were handed out on campuses and at college fairs, targeting new students and faculty.

Researchers also looked at 188 university websites, excluding historically Black colleges and universities, sorting DEI statements into ‘instrumental’ and ‘moral’ buckets.

The first several studies revealed the most significant finding: The most common approach to diversity in higher education ironically reflects the preferences of, and advances the expected outcomes, of white Americans. Overall, white participants felt they would receive more educational value from, belong more at, and have their social identities threatened less at universities employing the instrumental approach. In contrast, Black participants preferred and felt they would be more successful at morally motivated universities.

The instrumental approach isn’t just a matter of preference. Researchers found there were worse outcomes for Black students at institutions that adopted this approach:

When looking across university diversity statements, the researchers found that the instrumental approach was used more frequently. When linking this with graduation data, they saw that instrumental approaches also corresponded with worse graduation rates for Black students, especially when universities’ use of moral rationales was low. A similar pattern was found among Hispanic students’ graduation rates, as well.

There are caveats to the findings, researchers say. For starters, diversity statements aren’t the sole drivers of reduced morale and disparities, rather, they reflect institutional values. That, in turn, can influence other aspects of university life that create disparities, including one-on-one interactions and institutional-level decision making.

“Diversity and inclusion efforts seem to gain traction when they serve to advance majority group interests,” Stacey Sinclair, professor of psychology and public affairs at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs said in a statement.

“Students, universities, and policymakers should consider cultivating a culture that values diversity for a more balanced mix of reasons.”

One more thing: In the last section we said DEI programs appear to be catering to white people — but that isn’t always the case. DEI programs, on the whole, tend to cater to the white majority, i.e., (mostly) male, able-bodied, and cis-gender.

We’ve said many times before that most DEI programs erase disability.

These stats aren’t based in academia, but a December analysis of international data by the Valuable 500 found only 3 per cent of media articles discussing diversity reference disability, a statistic that has only risen by 1 per cent over the past five years.

That’s despite the fact that, according to the World Economic Forum, approximately 15 per cent of the population — or 1 in 7 people — live with some form of disability.

Non-binary students tend to be overlooked as well, not just in DEI initiatives but in academia as a whole.

Even though a growing number of people are identifying as non-binary, many academic studies predominantely recruit “male” and “female” participants, often neglecting to include the non-binary experience, making it difficult to fully understand how discrimination impacts this intersectional demographic.

While the broader push to create more diverse and inclusive spaces is welcome, performative initiatives can be damaging. Authentic allyship only happens when white, cis-gendered and able-bodied administrators are willing to take a step back and incorporate ideas from people who do not look like them.