NASA proposes new radiation exposure limits to allow women to spend more time in space

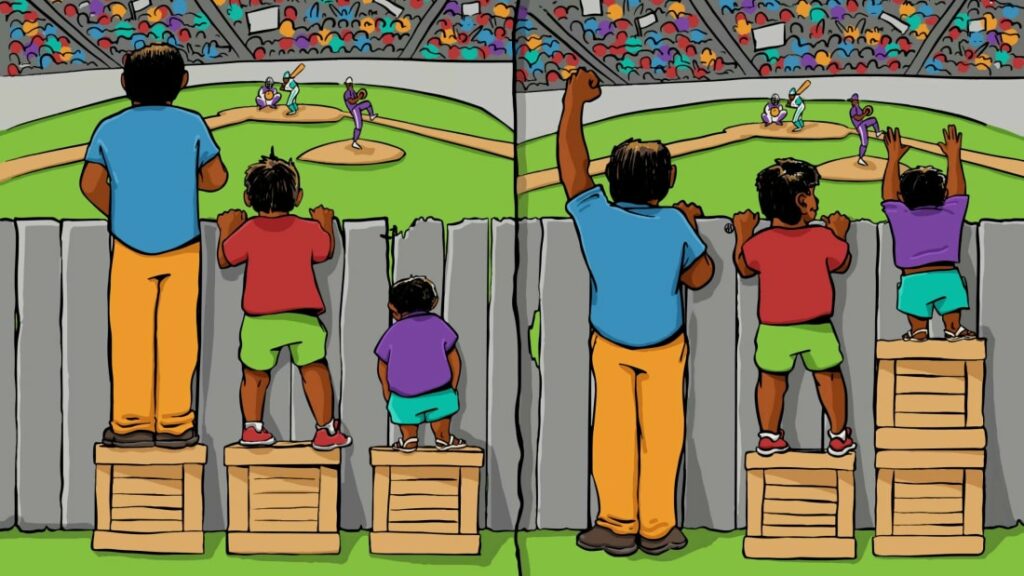

There’s a difference between ‘equity and ‘equality.’ One of the best visual representations we’ve seen of this concept was created by Angus Maguire for the Interaction Institute for Social Change:

This is a theme we’ve explored many times on We Rep STEM: True diversity and inclusion means all capable individuals have the resources, accommodation, and support needed to succeed.

Here’s an example of a move in that direction, courtesy of NASA. The space agency has just received an endorsement in the form of a report from the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine for its plans to revise its radiation exposure standards, limiting all astronauts to 600 millisieverts of radiation exposure throughout their career.

The current lifetime exposure limits range based on age and gender, from 180 millisieverts for a 30-year-old woman to 700 millisieverts for a 60-year-old man. The guidelines limit the risk of radiation exposure-induced death (REID) to 3 per cent with a confidence level of 95 per cent, Space News says.

Clearly, the old guidelines favoured older, male astronauts — an issue female astronauts have been sounding the alarm on for some time.

“A female will fly only 45 to 50 percent of the missions that a male can fly,” former astronaut Peggy Whitson told Space.com in 2013.

NASA’s new proposed standard limits all astronauts to the maximum allowed dosage for a 35-year-old woman, an important move as NASA gears up for renewed lunar missions and eventual missions to Mars.

“Women will not be penalized because they are, under the old model, at higher risk,” Paul Locke, an environmental health expert at Johns Hopkins University who was not involved with NASA’s proposal or the report, told Science.

But there are still many unknowns about deep space travel. For starters, humanity hasn’t ventured far from low-Earth orbit, and much of our understanding of radiation exposure limits comes from Earth-bound studies. Data from atomic bomb survivors people who work in high-radiation settings, like uranium miners, serves as the basis for current modelling on radiation exposure risk.

Astronauts travelling to Mars would be bombarded with a lot of radiation, around 1000 millisieverts, Science says, far exceeding NASA’s lifetime limit.

The report suggests implementing a colour-coded system when describing radiation exposure on future missions, with green being lowest-risk, yellow being higher-risk, and red missions exceeding lifetime exposure limits. Those willing to participate in red missions could be asked to sign a waiver — but there is worry this system may be too simplistic, and not accurately convey all of the complex processes that went into assigning the colour codes. Some critics say important health decisions shouldn’t be made in such a facile way, and the colour coding may influence some people to overlook important information that may help them make an informed decision.

Former astronaut Scott Kelly, who spent nearly a year in space, supports the system.

During his 20 year career, he was exposed to 240 millisieverts of radiation, raising his cancer risk by about 1.4 per cent.

“There are so many factors in whether you get a fatal disease,” he said via Science.

“You’re accepting a lot of other risks by flying in space, and this one is not the biggest.”