Improving access to education by making Braille textbooks cheaper and easier to produce

Currently, textbooks are converted to Braille by trained people who manually re-type the printed version — a process that is time-consuming and expensive.

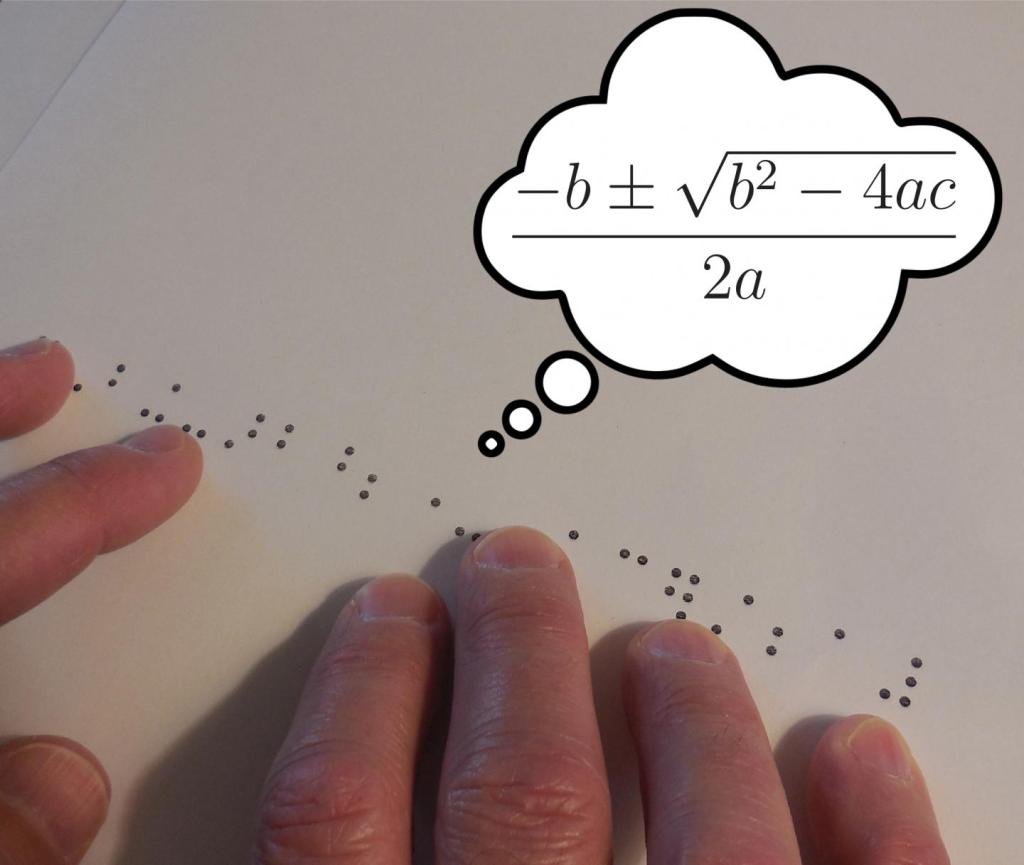

It’s just one of many challenges visually-impaired students face. While text-to-speech technology can alleviate some pressure, many visually-impaired students need to “feel” a textbook to learn, not unlike non-impaired students who need to stare at a formula to understand it.

Now, a team of researchers is working to make Braille textbooks easy to produce and widely accessible, and they’re doing it with the help of existing technologies.

Lead researcher Martha Siegel says her project was inspired by a blind student who required a textbook for a course. While she was able to order it, it took six months and several thousand dollars to produce, causing a significant delay in her studies.

RELATED: Number of students with disabilities on the rise

“Mathematics teachers who have worked with visually impaired students understand the unique challenges they face,” said Henry Warchall, Senior Adviser in the Division of Mathematical Sciences at the National Science Foundation (NSF), in a statement.

“By developing an automated way to create Braille mathematics textbooks, this project is making mathematics significantly more accessible, advancing NSF’s goal of broadening participation in the nation’s scientific enterprise.”

For now, the team is focusing on math textbooks — a challenging endeavour, given the fact that formulas are often explained through visual cues like graphs and diagrams.

Siegel teamed up with Al Maneki, a retired, blind NSA mathematician who serves as senior STEM advisor to the National Federation of the Blind, and Alexei Kolesnikov of Towson University for the project.

The structural components of the Braille books are generated using the PreTeXt authoring system which was invented by Rob Beezer, a math professor at the University of Puget Sound.

“This project is about equity and equal access to knowledge.”

Martha Siegel, a Professor Emerita from Towson University in Maryland

Beezer added Braille as an output format in his system — meaning every book written using PreTeXt can be easily converted to Braille, which can then be printed into a physical format. To date, about 100 books have been written using the system.

Braille math formulas are being created with the help of MathJax and Volker Sorge of the School of Computer Science. The system was originally designed to display math formulas on the web, but Sorge worked with the researchers to create accessibility features.

RELATED: Employers lose talent by overlooking workers with disabilities

“We have made great progress in having MathJax produce accessible math content on the web, so the conversion to Braille was a natural extension of that work,” he said.

Images and graphs remain a challenge, with researchers still devising ways to automatically convert them.

Siegel’s team says the automation employed by PreTeXt and MathJax will significantly reduce the time it takes to create a Braille textbook.

“This work is part of a growing effort to create high-quality free textbooks,” researchers said.

“Many of the textbooks authored with PreTeXt are available at no cost in highly interactive online versions, in addition to traditional PDF and printed versions. Having Braille as an additional format, produced automatically, will make these inexpensive textbooks also available to blind students.”

The next step — which already underway — is to initiate discussions with professional organizations to incorporate Braille output into their production systems.

In 2015, there were an estimated 7.29 million adults living with a visual disability, according to the National Federation for the Blind (NFB).

During the same year, about 42 per cent of blind or visually-impaired individuals were active in the workforce — but less than 15 per cent had a post-secondary degree and more than 25 per cent did not complete high school.

An estimated 29 per cent of visually impaired individuals live below the poverty line.

Original header image courtesy of the American Institute of Mathematics. Edited by We Rep STEM.