The world is not colour-blind. Pretending it is is dangerous and irresponsible.

This article was originally written for theconversation.com by Meghan L Mills, Birmingham-Southern College , for theconversation.com. Some dated information has been removed. Read the original article here.

Photo caption: Minneapolis, Minnesota November 15, 2015: On The morning of November 15, 2015 Jamar Clark was shot by Minneapolis Police. Neighbours say that Jamar was handcuffed while shot and that the police threatened residents to leave the scene immediately after the incident. Protesters met at the site of the shooting and marched to the 4th police precinct building. Caption: Wikipedia. Photo credit: Fibonacci Blue/Wikipedia.

The dominant approach to understanding racial inequality in the US today is “colour-blind racism.” This is the belief that racial inequality can be attributed only to issues considered to be “race-neutral”. In other words, because racial discrimination is now illegal, everyone is born with an equal opportunity to achieve the “American Dream,” no matter their race.

In comparison to the overt and legal racism prior to the Civil Rights movement, this “new” transformed type of racism is seemingly invisible, making meaningful societal discussions near impossible, and in turn perpetuating racial inequality, which then expresses itself, as we have seen, in these recent incidents.

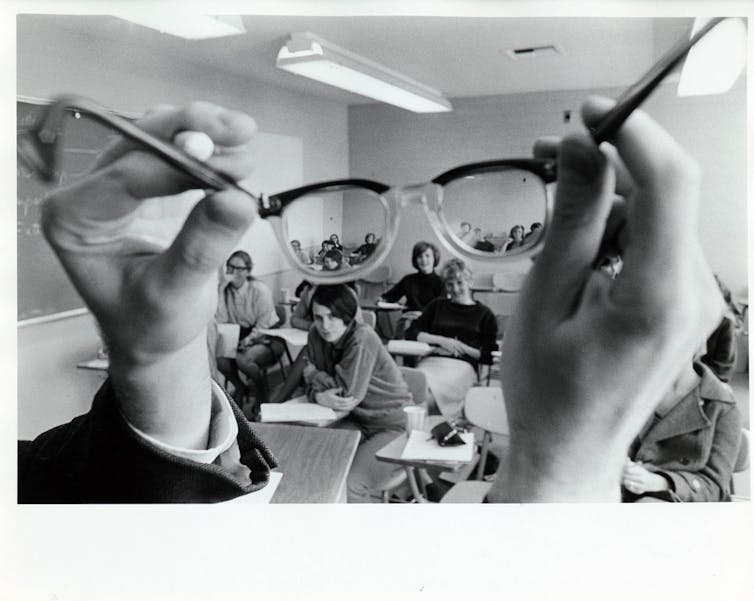

What about classrooms? Are adequate conversations around race taking place in that space? And how can scholars shape some of the discussions?

A clear example of “colour-blind racism” unexpectedly arose my first year as an assistant professor of sociology at Birmingham-Southern College (BSC) in Birmingham, Alabama.

Being a “Yankee,” I was warned in advance that my students at BSC would be more politically and socially conservative than what I was used to (coming from the University of New Hampshire).

However, midway into my first semester, I found that the majority of my students were able to critically engage in potentially controversial topics such as LGBT rights, health care reform and the legalization of marijuana. We also discussed the class inequality between them as middle- or upper-class students living within the gated “hilltop” campus and the surrounding lower social class neighbourhood immediately outside of the campus gates.

The real challenge arose when it came to discussing race in the classroom.

I struggled to get my students to address the “elephant in the room” – that the majority of the surrounding lower social class neighbourhood comprised racial minorities, whereas the majority of my students and BSC professors, including myself, benefited from “white privilege,” the often unacknowledged advantages with which whites are born, based solely on the colour of their skin.

I had incorrectly assumed that teaching in Birmingham, Alabama, with its rich social and cultural history of the Civil Rights movement and racial heterogeneity, would make discussing racial inequality one of the most engaging and meaningful discussions in the course.

My students refused to discuss race beyond a superficial level.

I found the majority of my students, primarily from the South, have been “socialized” to not discuss race because “race doesn’t matter” and we are (or should be) a “colour-blind” society.

This was illustrated by student responses such as “there is only one race: human” and “only racists see race” when asked in class whether race still matters. The responses were consistently given by students across my four classes.

Conversations with several of my faculty colleagues across disciplines also revealed that this was a common theme.

What I learned was that in order to get students to more effectively discuss issues of race, I needed to first address one of the most dangerous social myths perpetuating racial inequality in today’s society — that we are a “colour-blind” society.

I have modified my lesson on race to begin, not end, with a discussion of “colour-blind racism.” What I have found to be most critical to this discussion is challenging my students to apply their “sociological imaginations,” which can enable them to look at underlying social issues behind some recent news events.

As good sociologists-in-training, my students are asked to consider the larger social structural concerns (eg, poverty, institutional racism, the criminal justice system) instead of focusing on individuals (eg, Baltimore police officers, Rachael Dolezal, Dylann Roof).

My experiences in the classroom are by no means an isolated incident. Research consistently indicates this “colour-blind” ideology permeates education, politics, the criminal justice system, the media, etc.

This “colour-blind racism” is as dangerous as, if not more dangerous than, the overt racism during Jim Crow. It is for the most part invisible and easily overlooked in public discussions on social issues and therefore very effectively perpetuates racial inequality.

If the majority of my college students believe it is wrong to even “see” race, how can they be expected to meaningfully discuss larger issues of institutional racism and inequality? How can we as a society expect more meaningful social discussions and solutions?

As scholars, we need to emphasize to our students that race is a real thing, with real consequences. As long as we as a society continue avoiding “seeing” or meaningfully discussing race, we will continue to have Baltimore riots and Charleston shootings.![]()

Meghan L Mills, Assistant Professor of Sociology, Birmingham-Southern College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.