Systemic racism contributes to decline in urban biodiversity

The study's authors are appealing to readers to examine not only how we treat one another, but to consider how exclusionary practices damage the natural world.

NOTE: This article was originally published on September 2, 2020.

Racism and classism negatively impact the biodiversity and ecological health of urban plants and animals, according to a review paper published August 13 in Science, led by the University of Washington, with co-authors at the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Michigan.

“Racism is destroying our planet, and how we treat each other is essentially structural violence against our natural world,” lead author Christopher Schell, an assistant professor of urban ecology at the University of Washington Tacoma, said in a statement.

The study’s authors are appealing to readers to examine not only how we treat one another, but to consider how exclusionary practices damage the natural world.

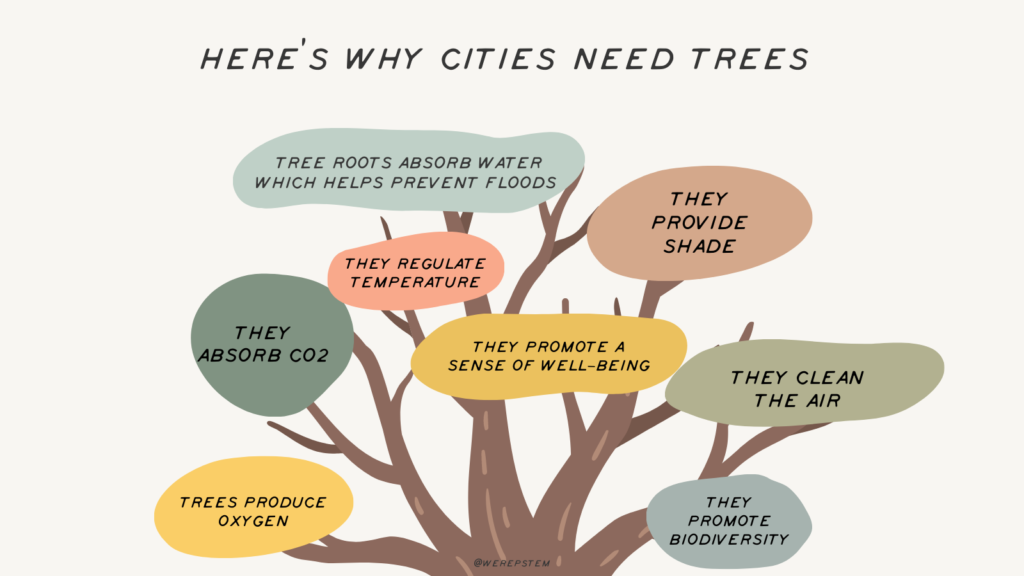

The paper cites several studies demonstrating how systemic racism negatively impacts the environment, including evidence there are fewer trees in racially-minoritized neighbourhoods in major U.S. and Canadian cities.

The lower-income areas tended to be closer to industrial or waste disposal sites than wealthier, majority-white neighbourhoods — a reality created by the racist practice of redlining, according to the study’s authors.

Over decades, the location of the lower-income neighbourhoods coupled with a lack of trees has contributed to warmer localized temperatures, more pollution, less biodiversity, and a higher incidence of disease-carrying pests that have evolved to survive harsh environments.

In a statement, the authors say they hope the findings will “show the scientific community that fundamental practices in science are based on systems that support white supremacy and perpetuate systemic racism.”

“I hope this paper will shine the light and create a paradigm shift in science,” Schell said.

“That means fundamentally changing how researchers do their science, which questions they ask, and realizing that their usual set of questions might be incomplete.”

Schell has seen several papers comparing biodiversity in urban and rural areas — but in many cases, organisms are only measured in wealthier areas and overlook the possibility of differences in neighbourhoods of different income levels.

Even if done unknowingly, he calls that type of science “negligent.”

“I hope many of my senior colleagues would start to rethink how they do their science,” Schell said.

“And for those scientists coming up, that this gives them the platform to say: ‘No, this is a legitimate question: How do we reduce, minimize, abolish racism in America?'”

The authors argue environmental issues should be re-examined to encompass societal problems.

Creating affordable housing, for example, could result in less turnover and fewer construction areas, leading to more ecological stability. Equitable access to green spaces could also help with plant and animal biodiversity.

“I’m hopeful things are going to happen because I have to be,” Schell said.

“We have the power to be activists in our own ways, in our own sectors, and we have the ability to motivate others to do the same.”