Future teachers more likely to view Black children as angry when compared to white students

The findings may help teachers' colleges and school boards devise bias elimination training programs.

Teachers-in-training cannot read the facial expressions of Black children as well as those of white kids and are more likely to view Black children as angry even when they are not, according to a study published July 2 in the journal Emotion.

The paper’s authors called the phenomenon “racialized anger bias.”

“Racialized anger bias means that people are seeing anger where none exists,” Amy Halberstadt, a corresponding author of the study and a professor of psychology at North Carolina State University, said in a statement.

“We saw this happening to Black adults in earlier research. This finding highlights the urgent need to address conscious and unconscious bias in educators.”

In an email to We Rep STEM, Halberstadt says that while the individual teachers who participated in the study aren’t likely racist, their unintentional biases are the product of a racist culture. When they enter the field, they will “have to be constantly reflective and vigilant” about how systemic racism affects teaching and interpersonal relationships.

“Mistakes can have serious repercussions for Black children because anger begets anger,” she says.

“A teacher who sees an angry child may be more likely to issue a consequence to that child. And that child might protest because it is unfair, which then leads to a more serious consequence, and then you have a cascade going. This can help to explain the finding that Black children received three times as many suspensions and expulsion as white children in school.”

Whether intentional or not, these misinterpretations can affect how a child feels about their teacher and school, and ultimately education.

“A critical question is: What is the impact on the child’s sense of self?” Halberstadt says.

For the study, the researchers surveyed 178 prospective teachers from three teacher training programs in the Southeastern U.S.

Eighty-nine per cent were women, and 70 per cent were white, with an average age of 22.48.

The overall composition of the group was consistent with the composition of public school teachers in the U.S., and they were training to teach in various grades, from early elementary to middle and high school.

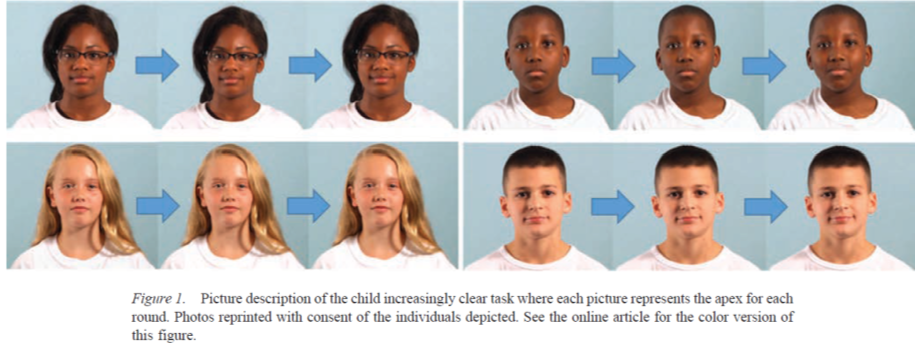

Participants were shown 72 short clips of child actors’ facial expressions, with video clips divided equally between boys and girls, and Black and white students.

Teachers were then asked to interpret the emotion displayed in each clip.

Researchers found the participants were 1.36 times more likely to demonstrate racialized anger bias — i.e., they were more likely to identify a non-angry child as angry — against Black children than against white children.

Participants were 1.16 times more likely to mistake a Black boy’s facial expressions for anger when compared to a white boy’s. They were 1.74 times more likely to misinterpret a Black girl’s facial expression for anger when compared to a white girl’s.

“We made sure that each expression was showing the desired emotion and only that emotion,” Halberstadt tells We Rep STEM.

“We were incredibly careful to ensure this so no one could say later ‘oh, maybe the black children were a little bit angry?’ no they weren’t.

We did not show them the fullest expression because we know that by third-grade children are masking a lot of what they feel, so the prospective teachers saw what they might see in the classroom. The prospective teachers were not given any additional information about the children.”

Experimenting in a highly-controlled setting was important, Halberstadt says, because it allows for the results to be used to help teachers and schools implement bias awareness training.

Halberstadt says the findings represent yet another form of systemic racism and is calling on educators to combat it through training and awareness.

“For teachers, so much is going on in the classroom constantly, and with 25-30 students in a room, there is no time,” she says.

“And yet, somehow to catch oneself in the moment and think: ‘Is this real or is it in my automatic assumptions?’ would be good. If not in the moment, then later, to have a conversation with the child to query and get some feedback – would be the next best thing. And for the long game, we think study groups or team efforts to catch this are important.”

The paper’s findings echo those from a June 2019 study out of Brown University.

In it, it was determined that Black elementary school children between the ages of 5 and 9 are more likely to be disciplined, suspended, or expelled compared to white students with similar behaviour traits.

Teacher and parent reports, school records, and survey data on children who attended elementary school in the U.S. between 2003 and 2009 were analyzed.

The records suggested that teachers’ different treatment of Black and white students was responsible for 46 per cent of the racial gap in expulsions and suspensions in the group studied.

“The idea that you can have two kids of different races misbehaving in similar ways and receiving different forms of punishment — one gets a slap on the wrist, say, and the other gets suspended — is a really important thing to understand socially,” Jayanti Owens, co-author of the study and an assistant professor of sociology at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown said in a statement.

“Subconsciously, we all have racial biases in different ways. This is one way in which those biases are manifesting in the classroom.”

Like what you see? Click here to learn how YOU can support We Rep STEM.