As the ADA turns 30, more needs to be done to support disabled individuals

Despite laws prohibiting disability discrimination, some individuals still face education and employment barriers.

Despite laws prohibiting disability discrimination, some individuals still face education and employment barriers.

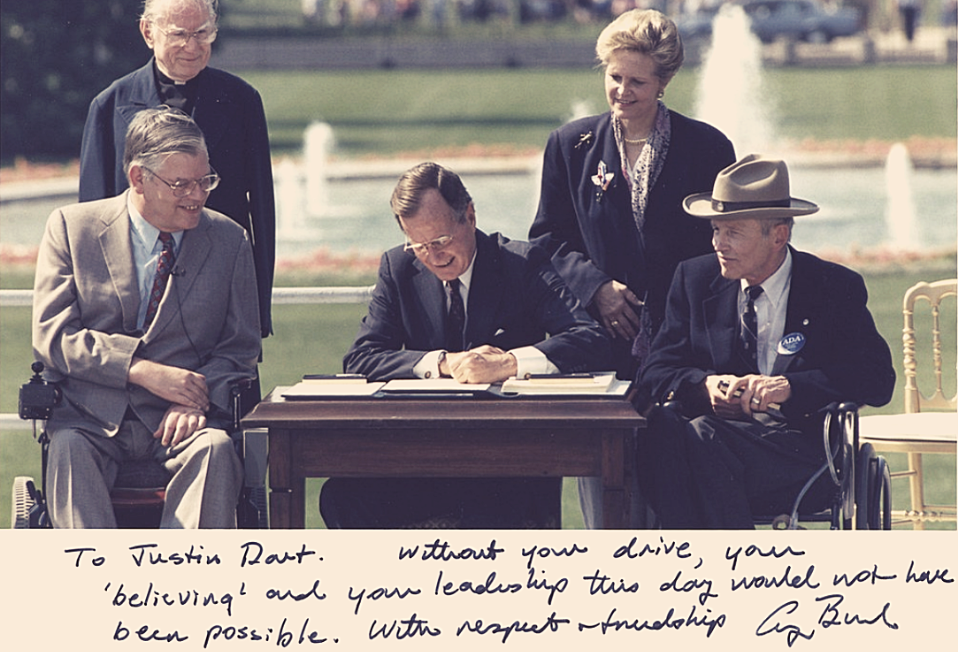

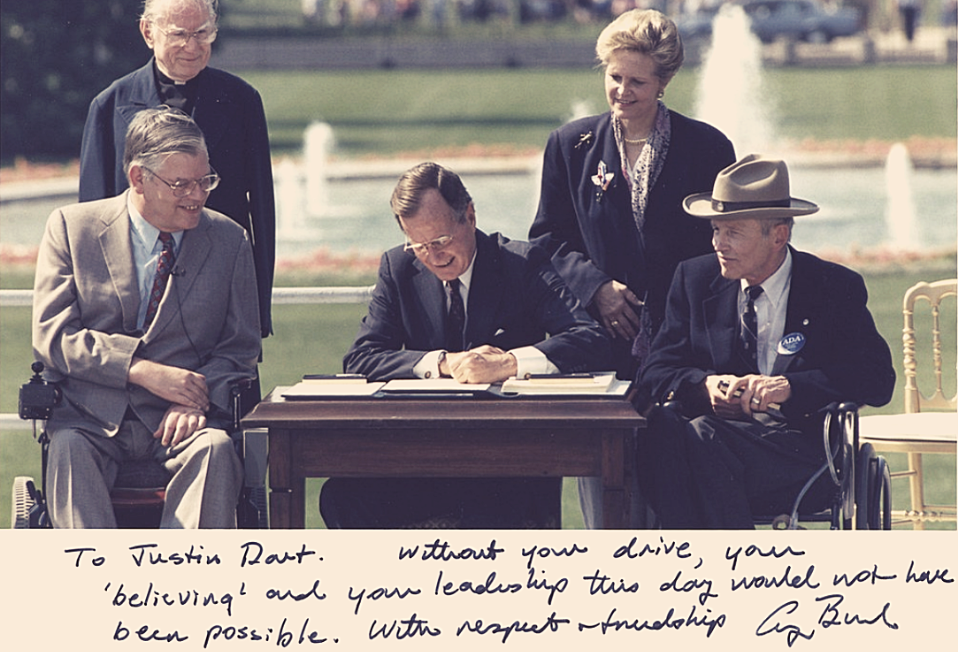

Photo of President George H. W. Bush signing the Americans with Disabilities Act inscribed to Justin Dart, Jr., 1990. Source: The National Museum of American History.

The American Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) turned 30 on July 26, celebrating the establishment of a law designed to ensure people with disabilities have equal rights and opportunities.

The ADA bans disability discrimination in employment, public accommodation, public services, transportation, and telecommunications.

A 2008 amendment broadened the definition of “disability” under the ADA, making it easier for an individual to seek ADA protection.

Despite the protections the ADA offers, many Americans living with disabilities continue to be subjected to overt and subtle forms of discrimination.

A recent study, for example, suggests some Airbnb hosts have been using a legal loophole to discriminate against disabled guests and deny them bookings.

Approximately 15 per cent of the world’s population — or 1 in 7 people — live with some form of disability. While a large portion of this group can work, it remains an underemployed segment.

In the European Union, about 60 per cent of disabled people are employed, compared to 82 per cent of the general population, the World Economic Forum says.

In the U.S., the stat is 37 per cent compared to 77 per cent, and an estimated 645,000 Canadians who are living with disabilities are unable to find work, despite being qualified to do so.

Workers with disabilities tend to earn less than their non-disabled colleagues. There are a variety of reasons for this, but one can be attributed to employer reluctance to create accommodating spaces. This can prevent disabled employees from taking part in career-building workshops, training sessions, and travel opportunities.

Some institutions have made efforts to better include students with disabilities. A November research letter in JAMA, for example, shows the number of U.S. medical students reporting a disability is on the rise — growing from 2.7 per cent to 4.6 per cent at the 64 medical schools surveyed between 2016 and 2019.

Part of the reason, according to researchers, could be due to medical schools’ efforts to create disability-friendly spaces. Nearly all of the students who participated in the research said their school made accommodations to support them.

But a follow-up report identifies disparities, suggesting that while medical schools may becoming more inclusive, the health care industry is not.

Between 2008 and 2018, it was found that federal funding for researchers with disabilities decreased by nearly one per cent, despite more disabled students entering medical school.

The report also found that disabled scientists are less likely to receive grant funding that those without a disability, indicating there may be bias in the grant review process.

Still, education barriers remain. Visually impaired students who use Braille may sometimes have to wait several months and pay several hundred dollars to secure textbooks.

And ableism on campuses can leave some feeling isolated.

“All students need to feel included in order to succeed in college. But when a student has a disability, inclusion can be more difficult to achieve,” writes Christa Bialka of Villanova University.

“One study shows students with disabilities participate in fewer extracurricular activities, like clubs or on-campus events, than non-disabled peers. This is due to a lack of social inclusion, the study states. It also stems from the fact that many colleges and university programs ‘focus mostly on academic and physical accessibility.‘ The social participation of students with disabilities gets less attention.”

Last January, a campaign called “The Valuable 500” was launched at the World Economic Forum assembly in Davos, Switzerland, aimed at increasing the number of disabled people in the workforce. Backed by the International Labour Organization and a consortium of businesses, the initiative is asking the CEOs of 500 companies to add disability inclusion to their agendas.

“It’s no longer good enough for companies to say ‘disability doesn’t fit with our brand’ or ‘it’s a good idea to explore next year’,” Valuable founder Caroline Casey said in a statement.

“Businesses cannot be truly inclusive if a disability is continuingly ignored on leadership agendas.”

According to Valuable, the estimated one billion people living with a disability worldwide hold an annual disposable income of $8 trillion, a staggering figure that businesses ignore at their own peril.

That — combined with the fact that 80 per cent of disabilities are acquired later in life — suggests disability prevalence is on the rise and signals an urgent need to create accommodating professional spaces.

“Organizations seeking a competitive edge in their industry should consider engaging people living with disabilities,” writes Silvia Bonaccio, professor of organizational behaviour and human resources management at the University of Ottawa.

“Businesses or workplaces that hire inclusively are more profitable. The bottom line is that hiring people with disabilities is good for business.”

Sign up for our newsletter and get our headlines delivered right to your inbox.